How to Find Cards Worth Regrading or Crossing: A Collector’s Guide

All Vintage Cards content is free. When you purchase through referral links on our site, we earn a commission. Learn more

Collectors are always on the hunt for the true holy grail. A vintage find at a yard sale or even a card show, the hope is that we can all find valuable cards at a significant discount. But what if I told you that the hunt is actually sitting right beneath your eyes and that the opportunities are more plentiful than you ever imagined?

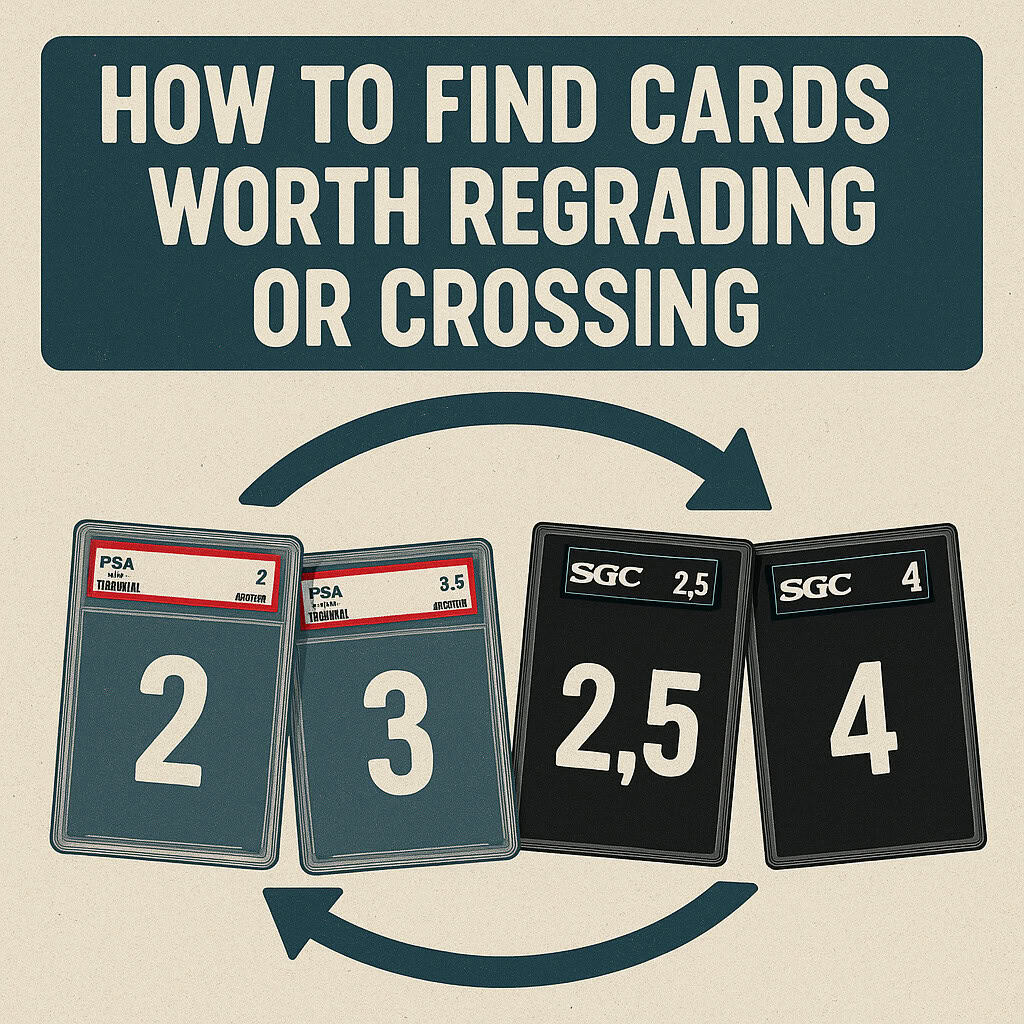

Enter the strategy of regrading, or crossing over, in which collectors identify undergraded cards that can be upgraded, ultimately making any card significantly more valuable in the process.

First lets do a quick terminology recap for those newer to the hobby.

Regrading: In simplest of terms, it is sending a card previously graded into the same or a different grading company, with the hopes of earning a better grade.

AVC Acquisitions Portal

Sell Your Card Collection

Skip the listing process and long wait times. Get a professional offer on your collection within 48 hours. See our buy list.

Cracking To Resubmit: Cracking is the process of removing a card from a graded case (aka ‘slab’) and with the intention of resubmitting it for re-grading with the same grading company.

Crossing-Over: Inolves usually ‘cracking’ the card from a case, or in some instances sending an existing graded slab to an entirely new grading company with the intention of earning a better grade than previously received.

Why This Strategy Works

The opportunity to regrade or cross cards exists for one simple reason: grading has never been perfectly consistent. Over the past thirty years, every grading company — and every individual grader within those companies — has applied slightly different standards.

Think about the real-world mechanics: you’ve got teams of human graders evaluating thousands of cards a day. There’s no exact mathematical formula for what a soft corner should mean, or how much a faint surface indentation should drop the grade. Even within the same company, two graders can reasonably reach different conclusions when faced with the same flaws. Multiply that across years, eras, staffing changes, and policy tweaks — and you naturally end up with variation.

Collectors often talk about “tough PSA years” or “lenient SGC windows,” and while some of that is anecdotal, there is truth behind it. BVG was once considered tighter on corners; PSA, at times, has been stricter about surface. But the real lesson isn’t to catalog the history — it’s simply to accept that grading drift is real and unavoidable.

And it’s human. A grader having an off day might be harsher on a card. A stack of submissions might create subtle time pressure. Even with official standards in place, it’s impossible to eliminate the human element.

Today, grading companies are incorporating AI-assisted imaging and consistency tools, which should reduce the more obvious misgrades we’ve seen in the past. But AI won’t erase subjectivity — and that’s precisely why upgrade opportunities continue to exist.

How To Spot An Undergraded Card

Most collectors focus on the number on the slab.

If you want to find upgrade candidates, you need to train yourself to ignore the label — and evaluate the card itself. That’s the heart of “buy the card, not the grade.” And it’s the only way to consistently spot cards that were undergraded, mislabeled, or simply sent through during a stricter grading period.

To do this well, you need confidence in identifying condition issues. If you’re not fully comfortable distinguishing a PSA 2 from a PSA 5, take time to study our grading guides — it will pay for itself tenfold.

When scouting online, your first move should always be the same:

Zoom in.

Check the borders, corners, back, and especially the surface — because the “grade killers” often hide where low-resolution photos don’t show them.

Once you’re zoomed in, here’s how to think about each part of the card — not as a series of bullet points, but as a flow of questions you ask yourself.

1. Centering (The Easiest Starting Point)

Centering is often the easiest win.

Some sets are notoriously off-center — 1969 Topps, 1971 Topps, 1957 Topps, T206 (miscuts everywhere).

If you find a low-grade example that is surprisingly well-centered for the issue, that’s your first green flag.

A “PSA 3” with great centering can sometimes beat a “PSA 5” with poor centering — both visually and in market value.

For example: here’s a PSA 8 Reggie Jackson 1969 Topps Rookie Card. Jackson’s rookie card is notoritous for having centering issues. This example is almost perfectly centered–maybe a very very slight diamond cut which probably held this card back by a grade. I’m not here to argue that this card should be a PSA 9 or 10, it shouldn’t. However a collector will pay a premium for this card, due to the centering.

2. Registration and Focus (Important, but secondary outside pre-war)

When colors line up cleanly, faces look sharp, and there’s no color fringing or doubling?

That’s a card with natural eye appeal — and graders absolutely take this into account.

Registration matters most on pre-war and early post-war issues, where multi-layer printing caused frequent misalignment.

By the 1960s and especially the 1970s–1990s, centering, corners, and surface flaws dominate the grade.

Some collectors don’t mind if a card is off-register, especially if it has cool effects, But registration can still help you spot value—however I see it as a secondary indicator rather than a primary one, only because it’s not always a major detractor from grade or value.

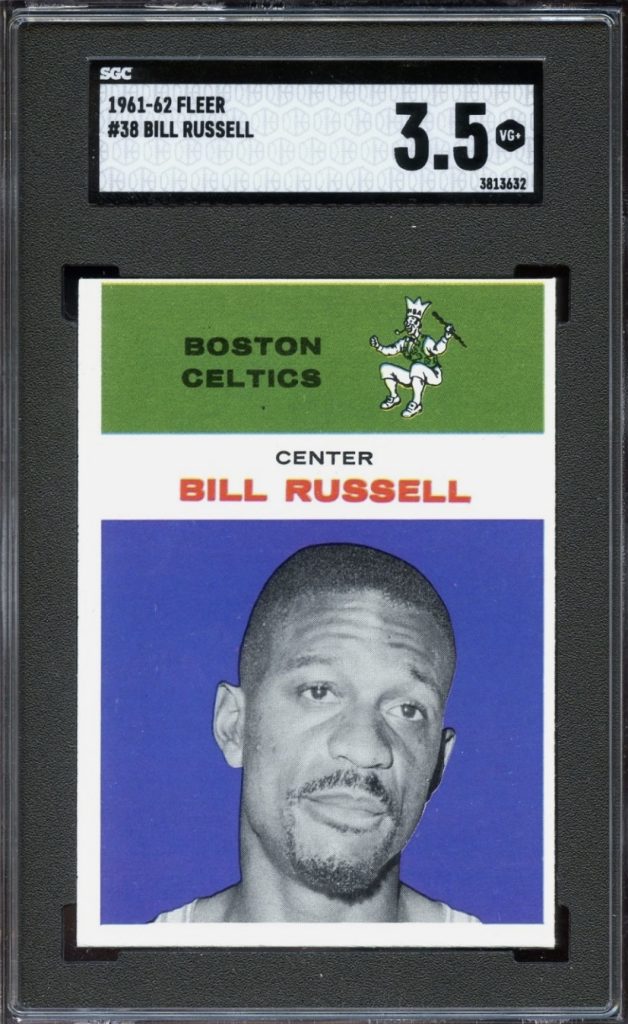

3. Corners and Edges (Where graders differ the most)

This is where graders often diverge.

One grader might hammer a card for slightly rounded corners.

Another might let it pass if the wear is consistent and honest.

What you’re looking for is uniformity.

One badly pinched corner? That’s a problem.

Four gently worn corners? Often much less of a grade limiter than people think.

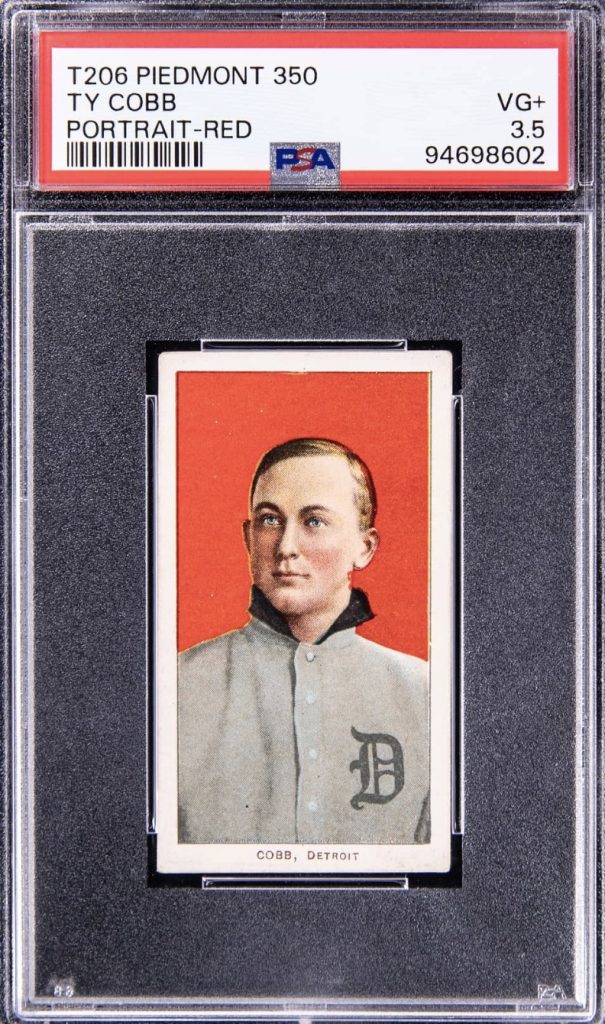

Here are two PSA 3.5 Ty Cobb T206 Red Portrait cards. Both are graded VGA 3.5+. One looks a lot cleaner and has whiter and sharper borders than the other. Which one would you rather have? I could argue that the card on the left deserves a higher grade, maybe a PSA 4, which in terms of this card is a big upgrade.

4. Surface

Surface flaws are the number one reason a card grades lower than it visually appears. Unlike centering or corners, surface issues can be subtle, hard to photograph, and easy to miss unless you know exactly what to look for.

When you’re evaluating surface, you’re really looking for four things:

— wrinkles or creases (sometimes extremely faint)

— print defects (snow, fish-eyes, print dots, registration lift)

— surface wear (dulling, scuffing, paper loss)

— stains (wax, gum, ink, moisture)

The key is to scan the card slowly. Start at the top, work your way down, and pay attention to how the surface reflects light. A clean surface should have a uniform sheen. A card with issues might show dull spots, disruptions in the gloss, or texture that looks “off.”

If you’re working from seller photos, ask for angled-light pictures or a short video showing the card tilted through different lighting. This exposes wrinkles, gloss wear, and impressions far better than a flat scan. It’s also worth asking directly whether any creases or surface marks exist that aren’t visible in the photos—because they often aren’t. And remember: images can be brightened or softened to disguise flaws, so treat unusually “flat” or overly bright photos with caution.

Ultimately, most truly undergraded cards share the same characteristics: the surface is clean, the gloss is intact, and there’s no hidden wrinkle lurking under the ink. When the surface is strong and the rest of the card looks better than the assigned grade, that’s where upgrade potential usually begins.

5. The Back

Collectors ignore card backs. Graders don’t.

Wax stains, paper loss, and erasures can kill a grade even when the front looks incredible.Turn the card over.

Does the back match the promise of the front?

If so, you’re moving into “upgrade candidate” territory.

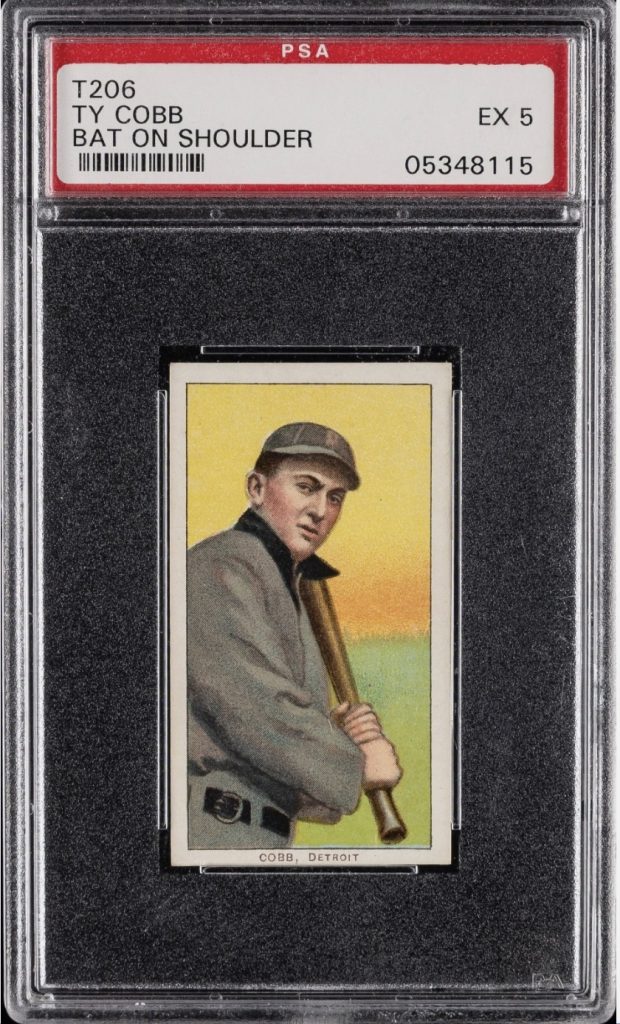

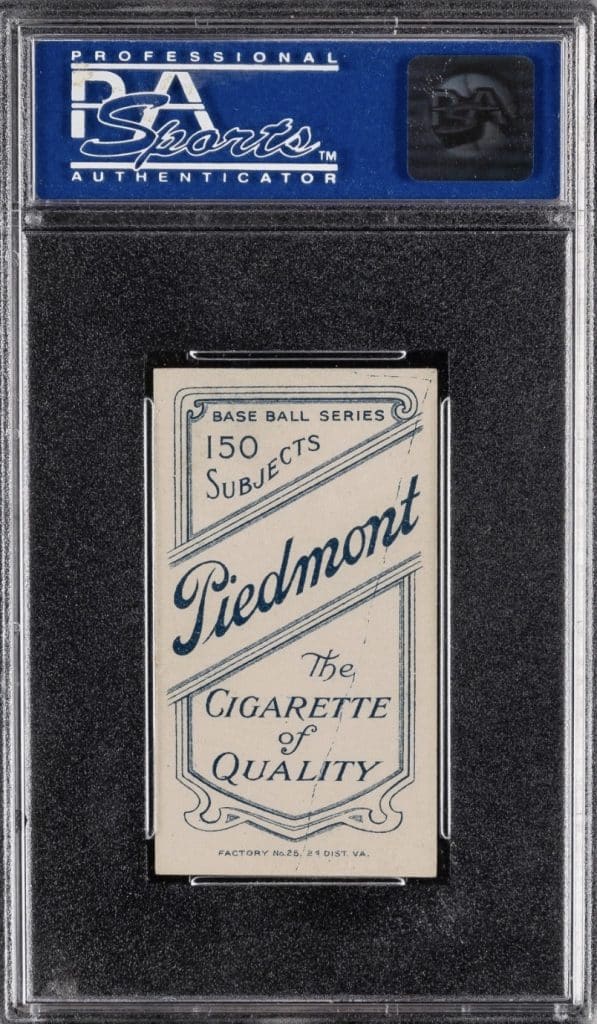

Here’s a beautiful PSA 5 Ty Cobb Bat On Shoulder Card which at first glance i thought seems like it could be worthy of a higher grade, probably a PSA 6 or even a PSA 7. However in examining the back of the card, there appears to be a blue print or ink line. For most T206 collectors, that line means nothing, however for a grader, it puts the card in the penalty box. This card definitely earns eye appeal but probalby not a regrade candidate.

Regrade vs Crossover — How to Choose the Right Path

Finding an undergraded card is just the first step. The next decision — how to upgrade it — matters just as much. Some collectors rush to crack and submit. Others always try a crossover. But the right move depends on three factors:

- How confident you are in your own grade assessment?

- Which grading company assigned the original grade?

- How old is the slab?

And then start with a simple question:

“If this card were graded fresh today, what grade do I truly think it deserves?”

If your answer is “one or two grades higher,” you likely have an upgrade candidate. From there, here’s how to pick your path:

Regrading with the Same Company

This can work — but mostly with older slabs. Older labels often reflect looser standards, inconsistent graders, or pre-modern processes.

Newer slabs?

Resubmitting directly to the same company rarely leads to a bump. Grading teams tend to stick close to recent decisions, especially if the slab generation is current.

If you do try this route, you must crack the card out first. Sending a card back in the same slab is essentially asking the company to publicly reverse itself — something they almost never do.

Crossing Over to a Different Company

This is where the real upside often lives.

Different companies weigh defects differently, and that variation creates opportunity:

- PSA → SGC:

SGC tends to be very consistent on vintage and may reward stronger overall eye appeal. - SGC → PSA:

Can make sense for key rookies where PSA liquidity and comps are significantly stronger. - PSA → BVG:

Sometimes helpful for vintage cards with slightly soft corners but strong centering.

Note that grading company’s will accept a crossover review for a card in an original slab from a different grading company. They just crack the card out of its slab and re-grade it. There is always the danger that the grading company damages the card in the process so be aware there are risks involved.

Read all about crossing over with PSA and Minimum Grade here

Using Minimum Grade (A Critical Step)

Any time you attempt a crossover — or even a regrade — you should use a Minimum Grade request.

A minimum grade tells the company:

“Only reholder or cross this card if it meets or exceeds this grade. Otherwise, return it untouched.”

This protects you from losing value.

Example:

If you believe your PSA 2 truly deserves an SGC 4:

- Set the Minimum Grade to SGC 4

- If SGC agrees with your assessment, great — you get the bump

- If not, the card comes back ungraded and your downside is zero (minus fees)

📈 ROI: What an Upgrade Is Actually Worth

A Real Case Study (With Numbers That Matter)

Spotting an undergraded card is valuable — but the real payoff is understanding the return on investment.

Here’s an example that’s realistic, replicable, and grounded in how the market actually works.

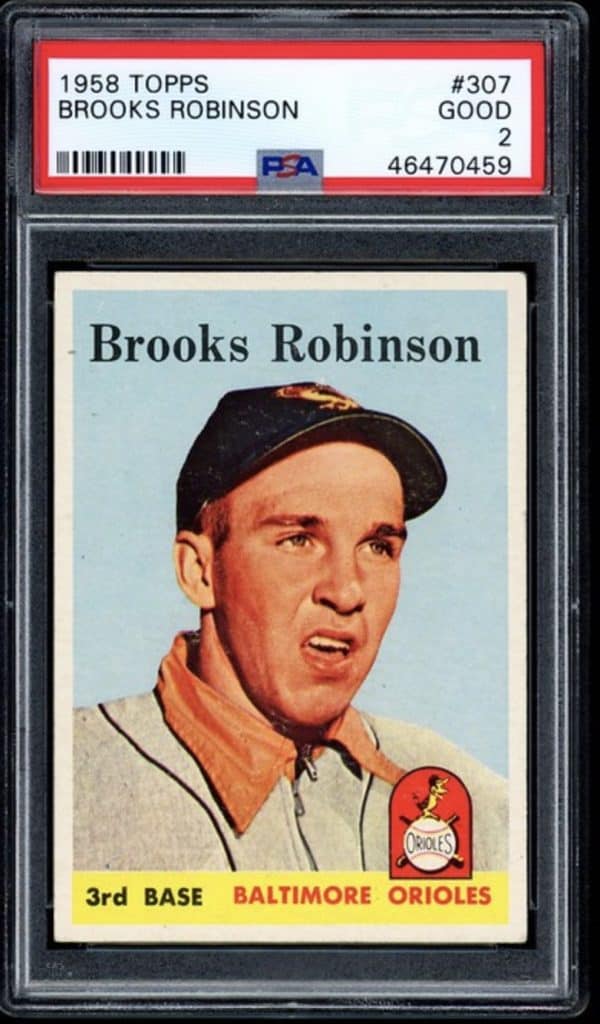

Case Study: PSA 2 → PSA 4 Crossover Upgrade

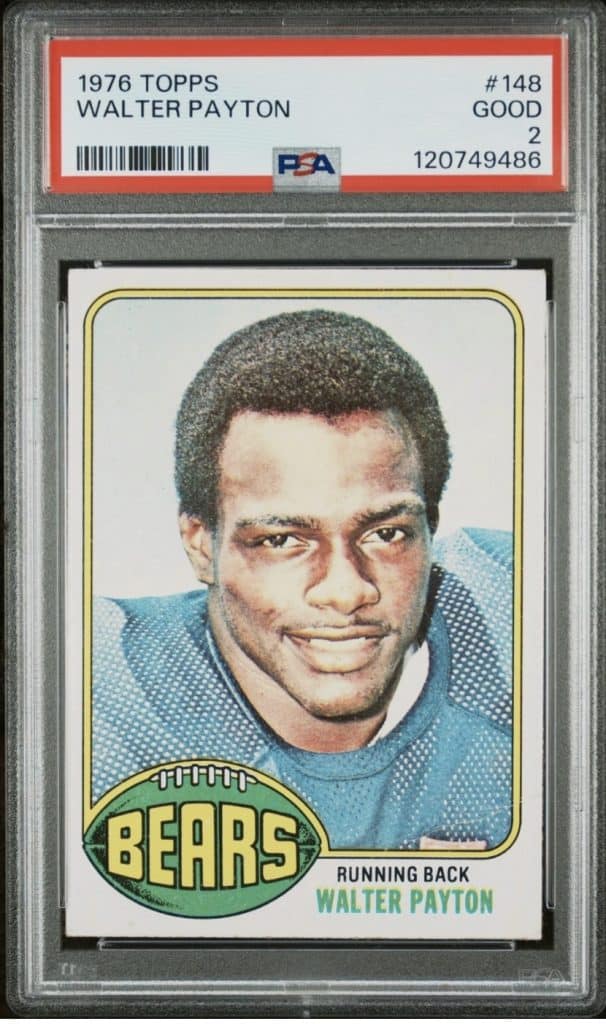

Card: 1976 Topps Walter Payton Rookie

Original Grade: PSA 2

Observed Eye Appeal: Centered, bold color, clean edges — likely a surface wrinkle hidden in older photos.

Market Prices (based on typical 2025 comps):

- PSA 2: ~$160

- PSA 3: ~$200

- PSA 4: ~$300

Let’s assume you spot a visually strong PSA 2 that looks like a mid-grade card.

You buy it for $160.

You believe the card has PSA 4 potential, but PSA is unlikely to change its own recent decision —

so you cross to SGC with a Minimum Grade of 4.

All-In Costs

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| Card purchase | $160 |

| Grading (SGC) | $28–$40 |

| Shipping/insurance both ways | $20–$25 |

| Total Cost | ~$210–$225 |

If It Crosses to SGC 4

Typical market value for SGC 4 Payton Rookie: $275

Net Return:

- Sell for $275

- All-in cost: ~$215

- Profit: ~$60

- ROI: ~28%

- Time invested: ~4+ weeks

So, not a bad return and note this does not include any selling fees…so it’s ok, is it worth it? Maybe, especially if you can repeat this process and earn this sort of return with higher dollar value cards. The return would likely. be higher if you were going the opposite way– for example from SGC to PSA, as PSA graded cards sell for a premium.

If It Doesn’t Cross

This is where the Minimum Grade protects you.

Worst case:

- You get the PSA 2 slab back

- You still own a strong-eye-appeal copy

- You can resell it for close to your original cost

- Your downside is basically the grading fee

The key is that this strategy has defined risk and asymmetric upside — exactly what collectors should want.

Bottom Line

Upgrading a card isn’t guesswork — it’s a skill.

If you train your eye, focus on true condition, and avoid getting hypnotized by the label, you’ll find cards that are graded too low more often than you think.

The formula is simple:

- Spot a card that looks better than the grade.

- Confirm the surface isn’t hiding anything.

- Choose the right upgrade path (regrade or crossover).

- Protect yourself with a minimum grade.

Sometimes the payoff is small. Sometimes it’s huge. But the edge is real — and it’s available to any collector willing to slow down, look closely, and trust their own evaluation over the number on the flip.